A paper published in

PNAS in January of this year has been getting a fair bit of attention. The paper, by Plassman and colleages, is called

Marketing actions can modulate neural representations of experienced pleasantness, and the bottom line result is that experimental subjects rated the very same wines as more pleasant, and had greater activity in some brain regions, when that wine was presented as being more expensive.

The subjects of the experiment had been told that they were tasting five different wines, with known prices, where in fact two of the wines were repeated, each time at a different price (one at USD5 and 45, the other at USD10 and 90).

Among the other accounts of this research in the blogosphere see

Ben Goldacre,

Epistemist,

Neurocritic and

Mindhacks.

The result isn't particularly surprising, and it seems to me that some fairly obvious variations on the task would have helped get clearer on what is going on. Also, I find some of the ways the results are presented a little unhelpful.

First, let me say a bit more about how the study was conducted. Subjects rated wines (all Cabernet Sauvingnons) without price information to establish that ratings of the wines were reasonably consistent. They were. Under scanning, with squirts of wine delivered through plastic tubes, they made a series of ratings (of either 'pleasantness' or 'intensity' on a 6 point scale) interspersed with mouth rinsing. Every wine was presented along with its 'price', and subjects held the wine in their mouth for 10 seconds before rating it. One of the repeated wines was presented half of the time at actual price of USD5 and otherwise marked up to USD45. The other repeated wine was presented at its real price of USD90, and marked down to USD10.

Subjects rated the same wine as more pleasant when more expensive, and, as hypothesised, there was more activity in their medial orbitofrontal cortext (mOFC), because other studies suggest that it is in the business of representing 'experienced pleasantness'.

So far so good. But the authors open by saying that "A basic assumption in economics is that the experienced pleasantness (EP) from consuming a good depends only on its intrinsic properties and on the state of the individual." They give a citation for this claim, but as so often the citation is to another publication endorsing the same prejudice, rather than a piece of evidence from the history of economics or utility theory. Actually, even Bentham was quite emphatic that as well as direct determinants of the utility from an experience (intensity, duration, certainty and propinquity) but also three important relational properties - fecudity (the tendency of a pleasure to be accompanied by others), purity (the tendency of a pleasure not to be followed pain) and extent (the number of persons who share a pleasure).

So price could well be an indicator of fecundity or purity (suggesting fine rather than lousy food, toadying service, well-dressed dates, etc.) even to a Benthamite. I wonder if there will ever be a day when people can manage to report results like this without feeling the need to announce a caricature or worse outright misrepresentation of the history of economics.

An earlier (2004) paper in

Neuron, called

Neural Correlates of Behavioral Preference for Culturally Familiar Drinks by McClure and colleagues, is clearer, and covers related ground. McClure et al found that on average subjects liked Coke more when they knew what they were drinking, than when they didn't know whether it was Pepsi or Coke. In their case the neural correlates of the marketing related preference weren't the mOFC, but a set of areas including the hippocampus and the ventro-medial PFC.

We need more experiments to try to isolate effects of scarcity (for example telling subjects that what they were tasting came from one of two classes, set up so that one was much scarcer), as well as Bentham style fecundity, purity and extent. That would also help shed light on how the different components of prior beliefs are neurally implemented and how they interact.

Two more quibbles, then a speculation.

Quibble 1: The abstract of the Plassman paper, and some remarks in the paper, suggest that this has something to do with "decision making". Indirectly it probably does, but the subjects in the experiment didn't make any decisions at all - they merely reported ratings. The subjects in the McClure et al study did make decisions forced choices between Coke and Pepsi, where there was a definite opportunity cost to each choice.

We just don't know whether subjects would have kept on buying the "UDS90 wine" over the "USD10" wine having tasted both and when spending actual money. We know that people like

free wine more when they think it's expensive, and that's not the same thing at all.

Quibble 2: There's some plain sloppiness here, whether the fault of the authors or PNAS. On p1051 the text refers to figure 1D as representing data from the 'postscanning blind test' whereast the figure caption indicates that it is panel 1E that represents that data. On page 1053 it says that "Two of the three wines were administered twice, once identified by their actual retail price and once by a 900% markup (wine 1: $5 real retail price, $45 fictitious price) or a 900% reduction (wine 2: $90 real retail price, $10 fictitious price)." Yeah right, a 900% reduction of USD90 leaves you with ten dollars. There I was thinking that 10 was about 11 percent of 90.

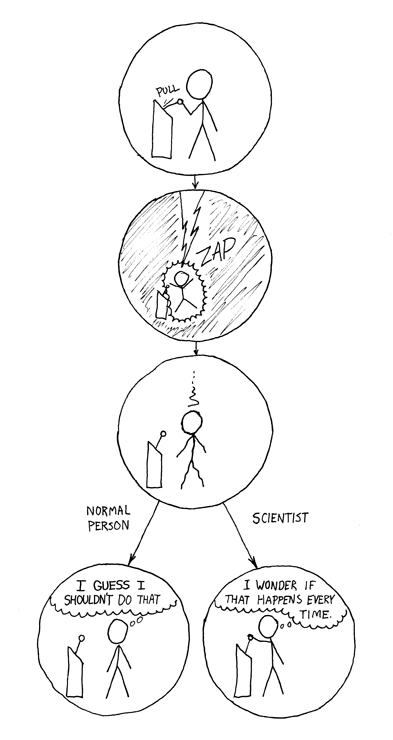

Then the speculation. I'd really like to see a roughly analogous experiment in the case of politics. Hotelling effects drive the content of at least some policies held by opposing parties in democracies towards near-indistinguishability. But citizens typically hold strong preferences between parties. Why not have subjects rate their level of agreement with policy claims and vary whether they're told that the policies are those of a Democrat or Republican, or a Tory or Labourite, etc.? I'd bet that the framing would make a difference, but I'm curious as to whether any coherent brain data would come along with that.

Oh, and one last thing. My occasional wine society (a bunch of friends who get together to eat and drink) are doing the opposite tomorrow night - a blind tasting to see if we can pick the expensive wines out of a set with 50% of the cheapest wines we can find. I'll report back. Odds are we'll drink too much and not discover anything new. Also, sadly, we don't have a brain scanner.

I don't know nearly enough physics to say anything useful about what is going on in particle physics. I do think that the Large Hadron Collider is spectacular, and beautiful and inspiring. The comparison with cathedrals is obvious, and I guess pretty regularly made (the words large hadron collider cathedral get about 11,000 Google hits). Really, though, this knocks old cathedrals into a cocked hat when you consider the extraordinary intellectual division of labour, and scientific and technical innovation demanded on so many fronts to pull it off. Don't get me wrong, I think some cathedrals are both beautiful and remarkable technical achievements, and understand that truly great minds worked on some of them. The LHC is just way, way, cooler.

I don't know nearly enough physics to say anything useful about what is going on in particle physics. I do think that the Large Hadron Collider is spectacular, and beautiful and inspiring. The comparison with cathedrals is obvious, and I guess pretty regularly made (the words large hadron collider cathedral get about 11,000 Google hits). Really, though, this knocks old cathedrals into a cocked hat when you consider the extraordinary intellectual division of labour, and scientific and technical innovation demanded on so many fronts to pull it off. Don't get me wrong, I think some cathedrals are both beautiful and remarkable technical achievements, and understand that truly great minds worked on some of them. The LHC is just way, way, cooler.